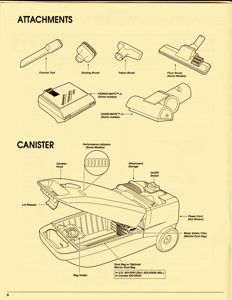

Out of uncharacteristic curiosity, I peeked at my wife’s copy of Human Anatomy and Physiology. I found myself in a section on tear ducts. I saw diagrams, descriptive terms, and explanations of processes. It reminded me of a vacuum cleaner owner’s manual: “This is what this part does. This is why this is here. Manufactured by so and so in such and such part of Mainland China. Designed by Sears in Kokomo, Indiana, USA. Limited warranty on parts and labor.”

Out of uncharacteristic curiosity, I peeked at my wife’s copy of Human Anatomy and Physiology. I found myself in a section on tear ducts. I saw diagrams, descriptive terms, and explanations of processes. It reminded me of a vacuum cleaner owner’s manual: “This is what this part does. This is why this is here. Manufactured by so and so in such and such part of Mainland China. Designed by Sears in Kokomo, Indiana, USA. Limited warranty on parts and labor.”

Whoever wrote the Human Anatomy book obviously did their homework. They didn’t just make the stuff up off the top of their heads or wake up one morning and say, “I think I’ll write a book on human anatomy. Today.” People study this stuff their whole lives. You have to be willing to work hard to learn it well, what to speak of teach it. What to speak of write a book about it.

What occurred to me was how the books authors are not the “manufacturer” of the human body—the way Sears is of the Kenmore Canister Vac. They don’t really know why things work the way they do, or even why they exist. But their tone was as authoritative as if they themselves are the designers of human bodies.

What occurred to me was how the books authors are not the “manufacturer” of the human body—the way Sears is of the Kenmore Canister Vac. They don’t really know why things work the way they do, or even why they exist. But their tone was as authoritative as if they themselves are the designers of human bodies.

You could say they’re doing the best they can with what little they do know or are able to observe, but I’m accustomed to want absolute knowledge of a thing. I ain’t satisfied until I feel like I’m getting the “doubtlessly factual, full explanation of everything about something from the omniscient point of view.” That’s one reason I became a Hare Krishna man.

I have no problem with people making detailed analyses of physical structures and the processes associated with them. They’re just describing what’s going on, apparent to the naked (or microscope-assisted) eye. That such descriptions are accepted as “all there is to be known” about any particular subject, though, or that such books as the one I casually glanced at are presented as truly authoritative is what I take issue with. They’re not authoritative. The authors didn’t create what they’re describing. Nor are they the actual manufacturer’s authorized representatives for creating explanatory literature.

Something about that sidelong glance into the anatomy text reminded me of the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, in which some numbskull drops a Coke bottle out of a plane flying over the desert. The bottle is discovered by the local people, who have never seen such an object before. The rest of the movie deals with how the desert dwellers try to make sense of this thing that’s inexplicably fallen out of the sky.

Something about that sidelong glance into the anatomy text reminded me of the movie The Gods Must Be Crazy, in which some numbskull drops a Coke bottle out of a plane flying over the desert. The bottle is discovered by the local people, who have never seen such an object before. The rest of the movie deals with how the desert dwellers try to make sense of this thing that’s inexplicably fallen out of the sky.

From the point of view of what I see presented as “science” these days, we humans have also essentially inexplicably “fallen out of the sky.” All our human-written textbooks, from psychology to astronomy to anatomy to biology, are something like the fictionalized Kalahari tribesmen’s attempts to explain—on the strength of grievously limited knowledge and power of understanding—what is beyond their ability to fully explain.

“What are we?” “How did we get here?” and “Why do we exist at all?” are three questions which cannot be answered—in any comprehensive, reasonable, and satisfactory way—by the equivalent of making up stories about a Coke bottle.

Maybe most people feel they can get by in life without reference to a body of knowledge and an intelligence that claims actual responsibility for causing our existence in the first place. But if I’m going to read about tear ducts, I want to know not only why our tear ducts work the way they do, but why they work at all, why they exist, what their proper use is, and what’s really worth crying about.

Be First to Comment