notes from a flatbed bicycle rickshaw ride, Jatipur/Govardhan, India, December 2010

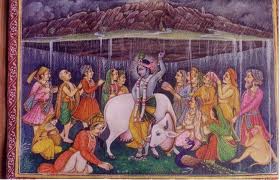

“Heading into town” in India isn’t the easiest maneuver for one who a) doesn’t know the language b) doesn’t know where he’s going c) doesn’t know the going price for travel. We decided, after an hour of back and forth about whether we should hire a three wheeled motor rickshaw or hop a ride with a swami, to climb aboard a bus headed back to Vrindavan and tell the driver to stop near where we wanted to go, which was the town of Govardhan, in the middle of Govardhan hill, which Krishna lifted back in the day.

Every ride I’ve taken anywhere here feels like the last ride I’ll take anywhere, and this particular bus ride was no exception. We sat up front on a bench facing the driver, so the only thing between my left side and the windshield was a foot of empty space. Ganesh was on the dashboard, looking at my white knuckles.

Our driver took a back road from Jatipur to Govardhan, a narrow dirt lane filled with cows, villagers with huge bundles of sticks on their heads, bicycles, and potholes filled with water. The video game Midtown Madness came to mind, as our huge vehicle rumbled and bumped down this tree-lined farm alley, and water buffaloes, cows and pedestrians gave way for fear of being crushed in our path.

We had no clear idea where we were going. We had a general idea that we were supposed to turn right at some point, then we would be in Govardhan town proper, then we’d need to make a left and ask for the Gaudiya Math, where we would have to ask for “anna jana,” or Internet Café. The whole time I had fear of the unknown boiling in my nerves, which wanted to be anywhere but where I was—preferably in front of a TV watching football with my father, eating cheese and crackers.

“Keep your eyes peeled for a bunch of rickshaws,” my wife said. I saw a big row of them around one corner. “Gaudiya Math,” our driver indicated, stopping the bus so we could get out. I don’t remember making eye contact with any of our fellow passengers, people with whom we’d just shared six days of dawn-to-dusk kirtans, classes, and discussions about the sweetness of Krishna and His relationships with His devotees. I was too freaked out to even say goodbye, as I stepped off the bus in the middle of what might as well have been one of the moons of Mars.

The sun was going down as we began down the dusty road full of motor rickshaws and roadside shops leading to the Govardhan Gaudiya Math, where at that very moment, their acharya, Bhaktivedanta Narayan Maharaj, was perhaps actively leaving his body at that very moment.

“Let’s stop here and ask for directions,” I suggested. We stepped through the gate, crowded with visitors and men sitting in chairs staring at us. “Jaya, jaya, Hare Krishna,” I attempted. I followed signs to “guest house office” and found two men sorting through a pile of room keys down one dark hallway. “Anna jana?” I asked, not even really knowing what the hell I was saying. “Internet?” “Oh, cyber café?” ask at office. Down stairs outside.” And so we went.

The gentleman at the front desk helpfully walked us out through the front gate and showed us “Past Chaitanya Math, next door.” And so we went.

The cyber Café was a little closet filled with huge, hungry mosquitoes. It reminded me of an old TV commercial for Off Insect Repellant. The floor was bare concrete, broken in places, and the room was lit by the classic single fluorescent bulb. The punctuation marks on the keyboard I was using were not in the same places as the one I’m typing on right now, so many of my sentences contained multiple forward slashes in front of words that I meant to capitalize.

Then the power went out.

“You please finish!” said the boy at the front, when the lights went black. Apparently all the computers ran off battery power in the case of power outages (which I imagine happen at least seventeen times a day) and this was officially the last power outage of the day. “You please close now!” I paid twenty rupees for our half hour and we stepped out again onto the dusty street. It was now night, and I didn’t have a flashlight.

(note to self: always keep flashlight in waist bag, no matter the time of day)

Now we had to deal with a) language barrier b) pitch blackness c) fear of being cheated by expert local rickshaw businessmen d) fear of being mugged in the dark.

“Let’s ask for help again at the Gaudiya Math,” I suggested.

“Whatever you think is right.”

At the front desk were some locals who didn’t seem to be charmed at the sight of us useless, helpless Westerners. “Rickshaw to Jatipur?” I asked, hoping some English was there.

“Why you going to Jatipur?”

“That’s where we’re staying.”

“Motor rickshaw, Maruti?”

“Ummmmm,” what’s a Maruti?” I asked my wife.

“I think it’s a truck.”

“Rickshaw,” I decided. “How much?”

“Twenty minutes, hundred rupees.”

“Should we go for it?”

“You go now,” said our guesthouse office manager. He bellowed for someone who came running.

“Hundred rupees only.” He confirmed.

“Dhanyavad (thanks), Hare Krishna” and we were off, following our driver.

The official local rickshaw wagon of Govardhan is a large, shallow wooden box on the back of a tricycle, sometimes lined with burlap rice bags for cushioning.

“This is going to be interesting,” I said, suddenly feeling very small, exposed, helpless and chilly with nothing whatsoever between me and the other plentiful, madcap traffic. I gripped the sides of the box for dear life.

Right away our driver stopped the rickshaw. “Oh, great, I thought. This is the end of my life. He’s going to get his friends who will rob and kill us. At least we’ll die at Govardhan.” He then began offering prayers as we stopped in front of the giant Govardhan Temple, the center of Govardhan Town, the very place where they say Krishna stood while lifting Govardhan Hill.

“Mandir,” he explained. I couldn’t see much of what was inside from my twisted, cross-legged, cramped perspective on the rickshaw, but I was able to turn and see the lights of the temple illuminating a tree trunk within, and the sounds of banging gongs and kirtan coming from within. I offered my respects with folded hands. “Jaya Jaya. Giriraj Maharaj ki jaya!” then we were off again, clinging to the back of a box on the back of a bike whose driver pedaled us through all manner of traffic, with no headlight, and only a little thumb bell to alert any other living being on the road in the dark of our approach.

Soon we turned off onto a dark side street and headed north toward Jatipur. This street was empty of all other traffic, which was good, because the chances of us being hit by oncoming traffic would be much lower, but bad, because we had no light, and the chances of us hitting a sleeping dog, pig, cow, or water buffalo in the middle of the road would be much greater.

Our driver turned around and displayed reddish, pan-soaked teeth. “Radhe! Radhe!” he shouted. What could we do but respond in kind? “Radhe! Radhe!” Our lives were in his hands, and he wasn’t even watching where he was going (not that he could even see anything anyway.) I imagined that, if he was worth his salt as a rickshaw driver, he’d taken this road millions of times, and could at this point literally drive with his eyes closed. I have nothing but steadily increasing respect for any Indian driver of any kind of vehicle.

We were able to see, on either side of the country road, an occasional candle or small fire, illuminating the faces of families who sat around it. The insides of roadside shops serving double duty as residences glowed red from the Coca-cola posters often serving as walls, or rows of Limca bottles became visible out of the darkness enveloping everywhere else but the night sky, which was full of stars.

“Kirtan! Kirtan!” Our driver turned around and yelled. He began singing a tune I knew—one that usually started with “Radhe Radhe Govinda, Govinda Radhe Radhe, Radhe Radhe Govinda, Govinda Radhe.” I caught on right away, and began chanting with him.

“He wants kirtan, let’s give him some kirtan,” I told my wife, who appeared to be very pleased to be on this wild, cold, bumpy, blind bike ride in the dark country roads of Govardhan. “Why not?” she said. “It may be the last bike ride we ever take anyway. Might as well go out chanting.”

We chanted until our voices got tired. Our driver punctuated our kirtan with his bell, and I slapped the sides of the box in rhythm, happy to take any measure that would hopefully elevate our driver’s spirits (I didn’t want to disappoint him) and alert others to our presence.

Soon we were back in a village, which I recognized as Jatipur, where we had been staying for the past week and a half during the retreat. Our driver dismounted at the base of a hill in the brick road, and walked us up the incline in between fluorescently lit shops still open and selling little silver packets of pan and betel nut. As soon as we reached the top of the hill, he jumped back on the bike and charged downhill again, past increasingly familiar sights, until we reached the gates of Ganga Dham, the ashram we were staying at. We finished our kirtan with one last “Shri Vrindavana Bihari Lal ki jaya! Jaya Jaya Sri Radheeeeeeee Shyam!” I happily paid him and looked gratefully up at the star-filled Govardhan night sky.

One short bike ride for this rickshaw walla. One giant leap of faith for me.

You forgot to mention that the riksha walla tried to squeeze a few more rupees out of us when he let us off.

wheres the like button?

Workin’ on it, workin’ on it! thanks! I (LIKE) your suggestion.

Another great piece. Hey, they already have this whole website where you can post stuff and people can see it. It already has “like” buttons and even has people you know already on it.

Wow! Really?

ED, I’m reading ‘A Walk in the Woods’ by Bill Bryson (his adventures on the Adirondack Trail) for the fifth time. I think I’m going to stop and just continue reading your posts instead. I love your stories.

Miss you more now, bro…

most excellent!